Marines in

Norway

Every year, new Dutch marines undergo their annual winter training in the forests of Northern Norway.

Marines in Norway

Every year, new Dutch marines undergo their annual winter training in the forests of Northern Norway.

Journalist Jelle Brandt Corstius and photographer Jeroen Toirkens visited the northenmost forests of the world. Four years, eight trips. Find other episodes of this journey here. Jelle elaborates on the project in this video.

Intense training

E

very year, new marines undergo their annual winter training in the forests of Northern Norway, the first few weeks of which focus on survival. This year around a thousand men are doing the training, apart from Dutch marines also Belgians and Germans, and some troops from the Land Forces. The training has been staged since 1972, initially by British and Dutch marines, who were tasked with defending NATO’s northern border in the case of a Russian invasion.

Trainees are expected to complete long marches on skis, with a pack weighing around thirty kilos. After a few weeks, shooting and combat exercises are also introduced, culminating in a large-scale military exercise against an imaginary enemy. Anyone who has successfully completed this intense training receives the ‘Panting Stag’, a coveted insignia amongst the marines. Survival in winter conditions is not only important in Europe, but also in other places to which the marines are subsequently posted, such as Afghanistan.

Due to the growing threat posed by Russia, in recent years more and more marines and other troops are being sent to do the winter training. The questions posed dur-ing the training are: how do you make the best use of the forest, what do you eat, where do you sleep, and above all: how do you keep yourself warm?

making fire

“This is the true tinder fungus, a mushroom that grows everywhere in the forests”, explains Cap-tain Roel Driessen.

“This stuff burns really well. Make sure you also have some birch bark on you. It dries out while you walk and you can start a fire with it. Gunpowder from your bullet also does the trick, if neces-sary. Tampons also work well.” There is laughter from the listening group, in which there is not a single woman to be seen. We are in the middle of the forest near Harstad, a coastal town near Narvik. There is a thick layer of snow on the ground; our flight was delayed by a day due to a snowstorm.

Driessen is standing beneath a tarpaulin at a table with flammable material. Around a hundred marines are sitting in the open air and watching patiently. They have just completed a several-hour march.

It is minus five, and the marines, overwhelmingly young men, are doing their best not to shiver. “Why is a fire important, apart from for the heat?”, Driessen asks. “For morale”, a marine shouts. “To purify water”, another calls out. “That’s right”, the instructor says. “Without wood you cannot survive.”

“We are back to the strength of the nineteen eighties”

After the fire instruction, the subject turns to food. A rack to hang a reindeer on is constructed out of wood gathered from the forest. The animal has been killed according to the rules by a local Sami herdsman, and is professionally skinned by Driessen. He hands a reindeer foot to the front row. “Pass it on. Feel what it’s like, a fresh piece of game.”

Some of the young men take the foot with distaste before passing it on. Eric Piwek, the training unit commander, looks on as the reindeer is filleted into pieces and explains why this important.

“Norway is a NATO country and has a strategic location. Due to global warming and the melting of the polar icecaps, new northern trade routes to China will be created, via the North Cape.’’ Piwek: “Given the way in which Russia has behaved in Crimea, we must be prepared for every eventuali-ty. Including for an invasion via the northern flank. And that means that participants must be pre-pared to fight in Arctic conditions. We are back to the strength of the nineteen eighties.”

surviving on the ice

“In the forest you have a shorter visibility range, which forces you to take decisions more quickly”, explains Captain Mark Brouwer. We are sitting in a Viking, a Swedish tracked vehicle which is jerkily working its way through the snow-covered mountains. We are on our way to a treeless plateau, because marines need to be able to survive there too. When we arrive, there is a new snowstorm that reduces our visibility to zero. A German marine who seems to appear out of nowhere takes us with him to a hole in the snow. We crawl into his shelter for the night, a snow hole. The roof consists of a tarpaulin and snow shoes, and there are two alcoves hacked out of the snow in which two marines can sleep. They sleep in shifts; the third one will sit on duty in the middle tonight. There is a candle in front of him, and if it goes out everyone needs to evacuate, as this means there is too little oxygen. Carbon monoxide poisoning poses perhaps the greatest threat, the servicemen explain. It is cramped and cold there, but considerably more comfortable than in the snowstorm raging above.

In the afternoon there is ice training. Marines are sent into a hole in the ice on skis with full packs and wearing white camouflage suits. The idea is to first throw your rucksack onto the ice, then to climb out yourself using the ski poles. You can climb out of the ice without a rucksack, but without your equipment you don’t survive, the instructor explains. A hundred men jump into the ice hole one after another. Everyone reacts differently. Some people climb out calmly, others start panick-ing and leave their rucksacks behind. That is what this training is all about: to prepare them for the unexpected.

The marines are being pushed in an icehole with full packing. When they have freed themselves they roll around in the snow to dry.

The marines are being pushed in an icehole with full packing. When they have freed themselves they roll around in the snow to dry.

a night in the forest

“Boys, this fire is going out. A fire needs love and attention, just like your girlfriend”, says moun-tain leader Ariën van de Kolk, who is making his night-time rounds of the forest. They sit spread out across the hill in groups of four. They have made a canopy out of pine branches and sit blink-ing around a small, smoking fire. “Why have you put snow on the branches?” “For insulation”, one of them says. “But the fire will melt the snow straight away.” Shaking his head, Van de Kolk con-tinues on his way.

“A fire needs love and attention, just like your girlfriend”

A little further on, they are doing better. There is a good fire burning, and the young men have piled up a series of branches that serve as a reflective screen, which makes more efficient use of the fire’s heat. A tin of potatoes hangs simmering above the fire. One of the marines is using his shovel as a kind of griddle with a piece of reindeer on it. “This fire makes me so happy after a long day in the cold”, he says. “I can stare at it for hours.”

Then it’s my turn to go to bed too. In the officer’s tent we are handed a bivy sack. There’s no need for a fire, Captain Brower assures us. “Tonight it definitely won’t dip below minus five. And don’t forget to get everything ready in advance, then you won’t have to do it outside in the cold.” With a flask of hot tea I walk to my sleeping place: a sloping tree trunk with a few pine branches above it. There is a bed of pine needles on the snow, like a kind of mattress. Of course I’ve forgotten my head torch, one of the numerous reasons why I’d be totally unsuited to life as a marine.

My shoes go into the bivy sack to prevent them from freezing, then I climb in after them, sleeping bag and all. It is rather claustrophobic beneath the branches, so I go to lie with my head under the stars. Taking a sip of tea is out of the question, as I’m determined not to go for a pee in the night. The flask keeps me warm. It’s pretty cosy actually, surrounded by the birches and the spruces, the lead characters in our project. I look up, at the aurora borealis, the Northern Lights. Green and yellow shapes that flicker dramatically, only to disappear again a few seconds later. In the background I can hear murmuring in German, English, Flemish and Dutch. The fire makes us brothers, I think, as I fall asleep.

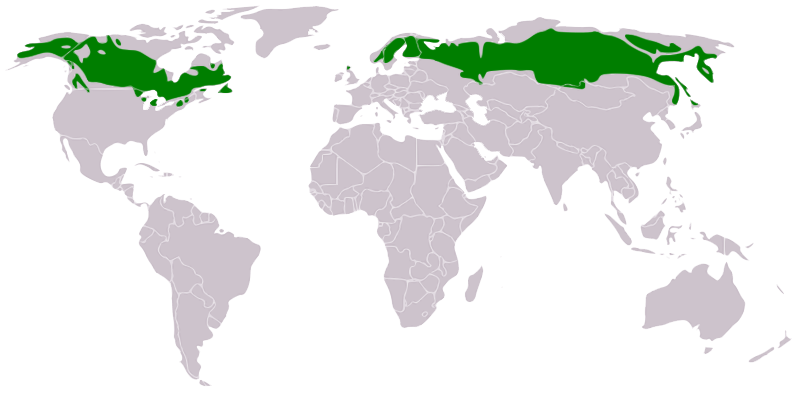

The boreal zone

The boreal forest is the largest vegetation zone on earth and comprises some 29% of the total forest area. With a surface area of some nine million square kilometres, it is considerably larger than the Amazon rainforest. Particularly in Russia, deforestation has increased dramatically since the fall of communism.

Boreal forests convert carbon dioxide into oxygen on a large scale. The average tree produces enough oxygen over a hundred-year period to allow a person to breathe for twenty years. Yet less than twelve per cent of these forests have protected status.

Due to climate change, the world of trees is changing. These changes are especially noticeable in the High North. For example, in 2016 the temperature in parts of Arctic Russia rose to between 6 and 7 degrees above the average.

The Borealis-project is supported by ASN Bank, Staatsbosbeheer (State Forest Management) and the Anchorage Museum in Alaska. Trouw is media partner. You can also support the project. More information at borealisproject.nl

TEXT: JELLE BRANDT CORSTIUS

PHOTOGRAPHY: JEROEN TOIRKENS

WEBSITE: GABRIELLA CODONESU thanks to JAN KRUIDHOF