above the japanese treetops

Japanese scientists are researching what the future of our forests will look like.

This is the second journey taken by journalist Jelle Brandt Corstius en photographer Jeroen Toirkens.

Above the japanese treetops

What will the future of our forests look like?

Journalist Jelle Brandt Corstius and photographer Jeroen Toirkens visited the northenmost forests of the world. Four years, eight trips. Find other episodes of this journey here. Jelle elaborates on the project in this video.

Why did you specifically decide to research trees?’ I ask. Tsutom Hiura, Researcher at the Univer-sity of Sapporo, his rhythm seems to have been thrown off by this apparently innocent question. After some consideration, he replies: ‘Because they are big, I think. And have an enormous impact on the rest of nature.’ They are certainly big. We are dangling from a crane in a gondola, about 25 metres above the ground. Hiura enjoys coming here. Beneath us lies the dense woodland of the Tomakomai Experimental Forest, a place where around thirty students and researchers are carry-ing out experiments on the vegetation. It is so densely forested here that it is pretty dark, to the point of claustrophobia.

That’s why it is so lovely to be hanging above the trees. In the distance lies the Tarumae volcano, which last erupted in 1982. The ash from the volcano creates a fertile soil on which trees can grow. The river than runs through the forest starts at the summit of the volcano. On the other side of the forest, smoke is rising up from the chimney of the paper factory, where many of the trees from the surrounding forests end up. And beneath us we can almost touch the crowns of the trees. There is no wind, it is totally still. This is a wonderful sight, intimate in a certain way.

The crane is part of a worldwide network of cranes that are used to study the crowns of trees, which, because of their height, are researched relatively little. Branches are marked to keep track of growth. Leaves are collected in nets. Down below, Hiura shows us a metal structure, which he has christened the ‘jungle-gym’. The structure is built around a group of trees, which makes them far easier to reach. Further on, there is hissing coming from beneath a tree. The sound is emana-ting from a valve that at intervals shuts off a PVC pipe protruding from the ground. ‘This piece of forest has been artificially heated an additional four degrees for nine years now. We do this with underground cables that emit the heat. Our aim is to mimic the warmed earth which we’ll have to deal with in the future.’ The pipe measures the CO2 level of the forest floor.

the ‘jungle-gym’ makes the trees better accesible. At some places in the forest extra nitrogen is injected in the soil.

‘Research into the forest floor is relatively scarce’, Hiura tells us. That is crazy, because the processes on the forest floor play a key role in the carbon cycle: the take-up and release of CO2 by plants and trees. Organic material on the forest floor produces CO2 and the temperature plays a role in this. For example, if the temperature this century rises by two degrees Celsius, the forest floor will produce exactly the same amount of extra CO2 as all human activities at this moment put together. In Tomakomai, they are studying how a raised temperature influences this CO2 production. For example, Dr Hiura and his team have discovered that a warm spring produces relatively more CO2 than a warm summer.

A member of staff from the university brings us to our lodgings. Even he can’t believe his eyes. It is a traditional Japanese guesthouse, which are becoming increasingly scarce: futon mattresses on reed mats. A yukata, a light kimono, is hanging on the coat hook. The staff member gestures to a Japanese bath that has already been filled with boiling hot water. We should take a bath and put on the yukata for dinner.

Once dressed in the yukata, I go and sit on the floor. One of the shojis — wooden sliding doors co-vered with rice paper — is slightly open. As the sun sets I sit in front of the crack. Outside there is a beautiful oak tree. Later I come to understand that shojis are often deliberately left partially open to focus attention on a beautiful mountain, river or tree.

The next morning, a busload of first-year students arrives. Yesterday they visited the Tarumae volcano, and today they will be given a tour by Dr Hiura. Communication proves difficult; it is not entirely clear to me whether they do not speak English, or whether they are simply shy. We drive to a place where additional nitrogen is being injected into the floor. The group listens politely. This is the next generation of researchers, who will need to be prepared for a changing world — higher temperatures, more unpredictable and more severe weather, and the disruptive effects that this will have on nature.

Tomakomai lies on the south coast of Hokkaido, Japan’s second-largest and most densely popula-ted island. Only in 1947 did it become a fully-fledged province of Japan. After the war, the popula-tion of the island increased due to the influx of Japanese refugees from the overseas territories. But the island is still empty by Japanese standards. We drive northwards through a mountainous landscape. The traffic thins out and the motorway becomes a provincial road. Standing beside the embankment are large metal installations designed to keep the snow off the roads during a snow-storm. At the end of the day, we arrive in the small town of Teshio. Due to a whole series of mis-communications, Jeroen and I walk into a school building. The head-teacher tells us that the popu-lation of Teshio has declined; the school now has just seven pupils. So the head-teacher has all the time in the world to accompany us to the building next door: this is the head office of Teshio’s experimental forest, run by Kentaro Takagi.

Proudly, Takagi explains that this is Japan’s northernmost forest, and one of the coldest places. Russia is not far from here and an offshoot of the boreal forest of Sakhalin runs through into Japan here. The question is how long this forest will continue to exist. Young pines are increasingly being challenged by an exotic species that is advancing from the south of Japan: the dwarf bamboo. The plant now covers around 80 per cent of the forest. ‘We call it sasa’, says Takagi. He immediately takes us with him to his forest. Before the bends in the winding road, Takagi hoots for cars that never come. Here the problem suddenly becomes clear: the ground beneath the pines is over-grown with the dwarf bamboo. ‘We expect the dwarf bamboo to supplant the pines,’ Takagi says. ‘Due to global warming, there will be fewer and fewer days with snow. A layer of snow protects young pines from the first cold. Without this layer of snow, the pines will not survive it, but the bamboo will.’

I ask Takagi how he survives the winters here. He smiles and hands me a piece of paper with the address of an onsen, a Japanese bathhouse. Later that day, we meet Simeon Bryanin from the In-stitute for Geology in the Siberian city of Blagoveshensk, who is carrying out his doctoral research here into the growth of tree roots. Just like the crowns, the roots are researched relatively little in the scientific world. Out of sight, out of mind. He pulls a cover off a trench in the ground and slides an ordinary office scanner into the trench. He uses this to make a scan of the tree roots once a week. By reviewing the scans one after another, he can see how the roots develop.

While Jeroen takes photos of the scanning, I walk a little way into the forest. It is not long before I am surrounded on all sides by the bamboo that is towering above me. That evening, Simeon takes us with him to the onsen; he goes there regularly. The onsen consists of three baths: one is incre-dibly hot, one is boiling hot, and one bath is red and smells of strawberries. I go and sit in the strawberry bath. Along the wall are taps and stools where men are sitting and washing themselves thoroughly. Clearly I was supposed to do that before I entered the bath; I excuse myself to the father and son who are also sitting in the bath. The father talks about the phenomenon, introduced in 1982 by the Japanese Ministry of Public Health, of shinrin-yoku, which loosely translates as a ‘forest bath’. In fact this is no more than an in-depth forest walk with a ‘forest therapist’ who leads you through the forest. They help you to make contact with the forest, through breathing techniques or simply by looking around you. This often takes place in a kind of bed, made in the hollow of a tree. Does this sound a little woolly? It’s not: a Japanese study from 2009 shows that a week in the forest leads to an improved immune system, lower blood pressure and less stress. And that’s genuinely how it feels after a week in the forest.

On the last day in Japan, we drive to Wakkanai, Japan’s northernmost town. The closer we get to Wakkanai, the clearer our reception of a Russian radio station becomes. The signs are written in both Japanese and Russian. In Wakkanai itself, a monument standing on a windy plain declares that this is Japan’s northernmost point. A jubilant Japanese cyclist arrives: he has cycled from Ja-pan’s southernmost point to Wakkanai — a real classic. On the other side of the water, the sun is shining on the mountains of Sakhalin; this was once called Karafuto, but after the Second World War, it became Russian. We go in search of Japan’s northernmost tree and find it just outside Ca-pe Soya. It is a small, low tree, surrounded by the inevitable dwarf bamboo. Will this tree still be standing there in twenty years’ time?

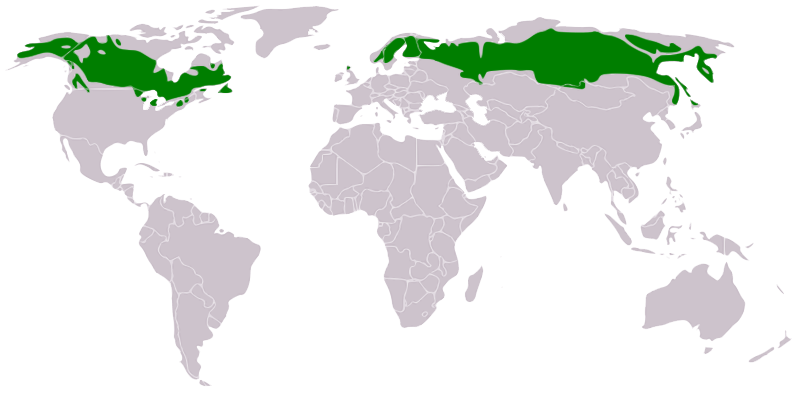

The boreal zone

The boreal forest is the largest vegetation zone on earth and comprises some 29% of the total forest area. With a surface area of some nine million square kilometres, it is considerably larger than the Amazon rainforest. Particularly in Russia, deforestation has increased dramatically since the fall of communism.

Boreal forests convert carbon dioxide into oxygen on a large scale. The average tree produces enough oxygen over a hundred-year period to allow a person to breathe for twenty years. Yet less than twelve per cent of these forests have protected status.

Due to climate change, the world of trees is changing. These changes are especially noticeable in the High North. For example, in 2016 the temperature in parts of Arctic Russia rose to between 6 and 7 degrees above the average.

The Borealis-project is supported by ASN Bank, Staatsbosbeheer (State Forest Management) and the Anchorage Museum in Alaska. Trouw is media partner. You can also support the project. More information at borealisproject.nl

TEKST: JELLE BRANDT CORSTIUS

FOTOGRAFIE: JEROEN TOIRKENS

WEBSITE: CHARLOT VERLOUW, MET DANK AAN JAN KRUIDHOF