How to bring back the trees to Scottish Highlands

The forest in the Scottish Highlands is dying out. Elderly trees are dying and young trees are being eaten. A group of volunteers is doing all it can to save the forest.

How to bring back the trees to the Scottish Highlands?

The forest in the Scottish Highlands is dying out. Elderly trees are dying and young trees are being eaten. A group of volunteers is doing all it can to save the forest.

Journalist Jelle Brandt Corstius and photographer Jeroen Toirkens visited the northenmost forests of the world. Four years, eight trips. Find other episodes of this journey here. Jelle elaborates on the project in this video.

A

round us is a beautiful, bare landscape, with above it clouds chasing through the blue sky. In the distance, yet another rain shower is heading our way. We are standing in a Scottish glen, an undu-lating valley, near the town of Drumnadrochit on the banks of Loch Ness. In the middle of the val-ley is a large Scots pine, standing solitary and majestic against the bare ground. This is precisely the beautiful Scotland of your imagination, and the reason why every year, hordes of nature lovers make a beeline for this place.

Alan Watson Featherstone from the organisation Trees for Life sees this spot very differently. Fea-therstone once worked for a mining company, but now his life is focused on preserving nature. ‘This tree fills me with sadness. It is a granny pine, an elderly tree. If you come here in twenty ye-ars’ time, there will be no trees left at all. At least, unless we take action ourselves. Our forest is dying out and there will be nothing in its place.’

At the beginning of the Middle Ages, large swathes of the country were still covered with Scots pine, a characteristic Scottish tree, as well as deciduous trees such as aspen, willow, oak and birch. But the population grew, and with it the demand for wood to build houses and keep them heated. Forests were obliged to make way for agricultural land. When Scotland also developed maritime ambitions, the clear-cutting was impossible to stop. The last Scots pines were felled, as they were essential for shipbuilding. Nothing much came of these maritime ambitions, because ultimately Scotland was defeated by its southern neighbour England.

During the so-called Highland Clearances in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as the trees disappeared so did the people. Under pressure from the English, entire Scottish communities were deported to the coast. In the Scottish Highlands, the English unleashed sheep that expertly mun-ched their way through and depleted the area. All that remained were the crofts, small parcels of land, and here and there a tree that by some miracle had survived the onslaught. Only in remote spots, steep mountainsides that were not suitable for farming, did small tufts of woodland survive.

Left: Frank Spencer-Nairn, landlord of Culligran Estate

Above: Frank Spencer-Nairn, landlord of Culligran Estate

These days, forestry is regulated. You might expect that with more responsible felling, the forests would regenerate by themselves. Around the granny pine, young spruces are shooting up from the ground everywhere. ‘But take a good look at this young pine tree’, says Featherstone as he bends down to examine one. The tiny tree is no more than ten centimetres high. The trunk is not growing straight upwards, do you see? That is because it is constantly being gnawed at, and then has to start afresh.’

Featherstone can tell from the buds on the trunk that it is already nine years old. In normal circumstances, a young tree would have stood here by now. But the circumstances are not normal.

The worst culprits are the red deer, of which there are some 400,000 in Scotland. They eat every-thing, including young conifers, especially in the winter when the animals are less choosy because of the snow cover. ‘The average age of a Scots pine is 250 years. Soon this granny pine will die and then we will be left with a barren expanse.’

Trees for Life are trying to change this. Since their foundation in 1989, they have planted around 1.5 million trees. For the first few years, these are fenced to protect them from hungry deer. When the trees are large enough, the fences can be removed.

We drive to Glen Affric, which has been a protected area since 2004 and where trees are being planted. This too was once a wasteland with granny trees, but now it is a beautiful forest. A wa-terfall supplies a constant stream of moisture in the form of water vapour. The ground is damp and swampy — some parts of Scotland are classified as rainforest. Hanging in between the trees are thick strands of lichen. ‘I see this as a time machine’, Featherstone explains. ‘This is what Scot-land must have looked like in the past. But if you look behind us here, that is commercial forest. Trees that are standing close together in straight lines. These are fast-growing varieties, imported from America. And now look at the other side. This tree has space to grow widthways. Every tree there has its own shape and character. That makes me happy.’

For his plan to bring back forests to the Scottish Highlands to succeed, collaboration with large landowners is essential. Five hundred people own more than half of Scotland, an abnormal per-centage. This is a legacy of the old clan system. It is only since the 1990s that Scotland has two national parks.

Not all large landowners are enthusiastic about more forests. This is because many people are dependent upon deer hunting, and it is difficult to hunt in a fenced forest without deer. And yet there are also exceptions, such as Frank Spencer-Nairn, the landlord of the Culligran Estate, situa-ted in the Strathfarrar Valley. Every day, he takes his dog for a long walk across his network of thirty kilometres of private roads. We are currently on the edge of his estate. An invisible border runs through the valley, and behind it the next estate begins. His neighbour is an oil sheikh who turns up a few times a year to shoot down a few red deer from a helicopter. In the oil sheikh’s valley, a herd of deer is grazing peacefully. It would seem that the sheikh is not at home.

‘Every tree has its own shape and character. That makes me happy’

Spencer-Nairn explains that every estate is obliged to kill a number of deer annually, to prevent over-population. This figure is decided upon every year at a landowners’ meeting. That is also the moment to talk about the expansion of Scottish forests. Spencer-Nairn: ‘The majority of large landowners are firmly opposed. For me it is different. I rent out houses on my land to nature lo-vers who come here to walk or for birdwatching. Then it’s actually an advantage to have a bit mo-re woodland.’

Along the road, he points to a piece of woodland bordered by a fence. The fences come from Trees for Life. This is a collaboration that benefits both parties — the landowner and the nature conservation association. The trees are still young, so the fencing will remain in place for a few more years.

The Scottish government is also determined to restore the old Caledonian forests. The goal is to reforest a quarter of Scotland by 2050. The current figure is 17 per cent, of which a large proporti-on is commercial forest. But there is huge resistance from the large landowners. They have found an unlikely ally in the mountaineering association, which would prefer the mountains of Scotland to stay bare. It is therefore questionable whether this goal will be achieved. This also depends on the number of deer, and the access that they have to the young forests.

If it were up to Trees for Life, then the target would certainly be reached. On a sheltered moun-tainside, volunteers are planting young aspens on an autumnal morning. The mountain slope in question lies in the Dundreggan Estate, a former hunting ground that Trees for Life has purchased in its entirety. The young trees are put into the ground with great care. The work is regularly inter-rupted by a heavy shower of rain, after which the sun comes out again. ‘Scotland is like the wea-ther: unpredictable and always changeable’, a volunteer observes. ‘In fifty years’ time, there will be a beautiful forest on this slope. So come back again then!’

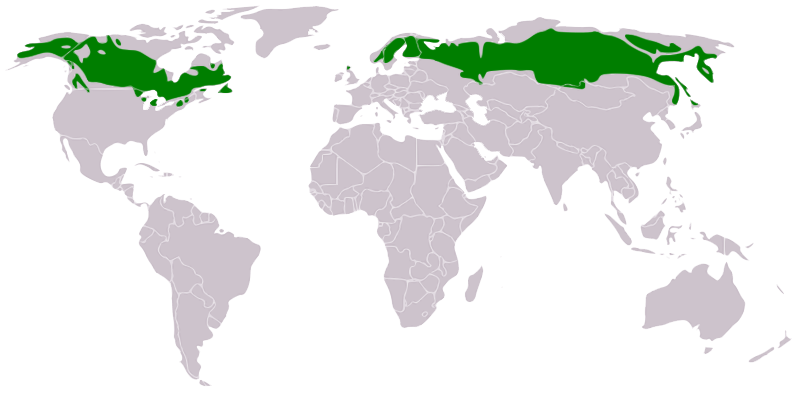

The boreal zone

The boreal forest is the largest vegetation zone on earth and comprises some 29% of the total forest area. With a surface area of some nine million square kilometres, it is considerably larger than the Amazon rainforest. Particularly in Russia, deforestation has increased dramatically since the fall of communism.

Boreal forests convert carbon dioxide into oxygen on a large scale. The average tree produces enough oxygen over a hundred-year period to allow a person to breathe for twenty years. Yet less than twelve per cent of these forests have protected status.

Due to climate change, the world of trees is changing. These changes are especially noticeable in the High North. For example, in 2016 the temperature in parts of Arctic Russia rose to between 6 and 7 degrees above the average.

The Borealis project requires a lot of travel, mostly by plane. To partially offset the CO2 emissions, Trees for Life has planted a piece of forest in Scotland on behalf of Toirkens and Brandt Corstius. In the Glen Affric valley, if things go well, there will be a new forest in about thirty years. For the time being, it is 165 “Borealis trees”, at the end of the project the forest will be further expanded to make Borealis CO2 neutral.

The Borealis-project is supported by ASN Bank, Staatsbosbeheer (State Forest Management) and the Anchorage Museum in Alaska. Trouw is media partner. You can also support the project. More information at borealisproject.nl

TEKST: JELLE BRANDT CORSTIUS

FOTOGRAFIE: JEROEN TOIRKENS

WEBSITE: DANUSIA SCHENKE, JAN KRUIDHOF EN SUSANNE POOT