Stacking wood as

an artform

Cutting wood in the Pasvik Valley in the far north east of Norway.

This is the first journey taken by journalist Jelle Brandt Corstius and photographer Jeroen Toirkens through the world’s northernmost forests.

stacking wood as art

In the Pasvik Valley, in the far north east of Norway, is just one road. Getting lost is impossible.

Journalist Jelle Brandt Corstius and photographer Jeroen Toirkens visited the northenmost forests of the world. Four years, eight trips. Find other episodes of this journey here. Jelle elaborates on the project in this video.

T

he chainsaw is whining and the blade is already touching the trunk when Svenn Randa suddenly switches it off. ‘Bird’s nest’, he says and points upwards. Five metres away there is another tree, and within thirty seconds the tree is falling to the ground with a crack. Randa lives on the other side of the road running past the campsite, our home for the coming week. We’ll be using this as our base for exploring the Pasvik Valley in the far north-east of Norway.

It is impossible to get lost here, as there is just one long, straight road running through the valley. There’s not much traffic, but it’s still a good idea to drive slowly because from time to time a rein-deer will shoot across the road. Each house along the road has its own story. Like the house where Randa, a retired lumberjack, lives. He may have retired, but this doesn’t mean that his timber fel-ling days are over yet. He shows us the cross-section of the trunk, which smells of resin, wood and vaguely of smoke due to the friction caused by the chain saw. The annual rings are close together. ‘It takes 180 years before trees are fully grown here. That’s a good deal longer than in the south, where it’s warmer,’ he explains to us as his grandson translates. It feels amazing to be holding a tree that first saw the light in 1836. At that point, this area was still untouched by the human hand. It was only in 1860 that the Pasvik Valley was colonised from the south.

Randa began working as a lumberjack at the age of twelve. This was just after the Second World War, and Finnmark, the north of Norway, was devastated. It was not until decades later that Nor-way would become one of the world’s richest countries thanks to its oil and gas reserves. At that point it was still a poverty-stricken place, and Finnmark was one of its poorest regions. ‘I remem-ber how the Germans burnt the wood supplies when the Red Army marched in. The fire raged for months. It was such a sinful waste.’ People managed to survive the period just after the war by bartering goods with one another. But in this area, warmth is just as important as water and food. Until recently, wood was an absolute prerequisite for living here. To stay warm people had to ven-ture deep into the woods, as the Germans had already cut down all the easily-accessible wood beside the road. First with horses, then with tractors and sledges. The 180-year old tree will also end up in the stove, probably during the winter when this region is plunged into a night that lasts for three months.

VOORRAAD

“R

anda still cuts down trees each winter for firewood, which he transports to his home by snow-mobile. I ask him whether all that wood dragging hasn’t taken its toll on his body. ‘On the con-trary, all that dragging is the reason why I’m still alive. If I’d spent my life sitting on the sofa in front of the TV then I’d probably be dead by now.’ He certainly looks healthy and spry for his 76 years. His ramrod straight back is not dissimilar to the mighty tree that he has just felled. After a long silence – with a Norwegian you can never be sure if they’ve finished answering or not – he continues: ‘Using your body, the fresh air. The winter is the best time of the year.’

We drive further along the road towards Svanhovd, from where the valley was colonised. Here is the only shop in the Pasvik Valley, where you can buy dodgy fruit for astronomical prices. We go past a house with a lavru in the garden – a traditional tent that is still used by the indigenous Sami people. In the house next door, a man is busy stacking firewood. He felled the timber himself in the winter, and it has just been processed into smaller logs at the sawmill. Egil Kalliainen is a rein-deer herder. At the moment, his herd is grazing on the tundra beside the sea in the north, where there is currently plenty of food. He is leaving the herd in peace for now, as calves have recently been born. So this is a good time to stockpile a supply of wood for the winter.

“The winter is the best time of the year”

Kalliainen stacks the wood so that it can air and dry. I had read somewhere that Norwegians have elevated the creation of woodpiles into an art form. And that before saying yes to a marriage pro-posal, Norwegian women will first check whether their potential life partner is any good at stack-ing wood. At the latter suggestion, Kalliainen falls about laughing, but he nods in acknowledgment of the former, although it is chiefly true of his generation. ‘The relationship with the forest is changing. Young people see the forest as a place for recreation, not as somewhere to exploit. They no longer know how to fell, stack and dry timber. Most have switched to electric stoves. These may be more expensive, but they are less labour intensive.’ As fewer and fewer trees are being felled, the forest is becoming denser, which makes it increasingly difficult to walk between the trees. Added to this are the effects of climate change: ‘The conifers are being supplanted by deciduous trees from further south. Before, the climate here was too extreme for these kinds of trees, but that is changing. The winters are warmer, shorter and wetter. Last year, there was so much snow that not even a moose could walk through it. Can you believe it?’

The last tree of Norway on the terrain of the police station or borderstation in Nyrud. On the other side the forests and water of Russia.

The warmth of fire

“B

ack at the campsite, as if she has been listening in to our conversation, the campsite manager points out an unremarkable flower to us. ‘That’s only supposed to bloom in a month’s time.’ She’s just been using the sauna, and she invites us to take a turn if we fancy it, as it’s still hot. In the sauna Jeroen throws another block of wood on the fire, and with some difficulty manages to get it going again. After sweating it out for a while, we jump into the lake. What is it about a wood fire? Why is it that you can stare at a campfire for hours? And why does fire feel so good? Why is the warmth different to what comes out of a radiator?

It’s eleven o’clock in the evening when the fire in the sauna finally goes out. Outside the sun is still shining cheerfully. It’s the end of May, and at this time of year the sun doesn’t set any more. The days never end, and the birds continue to sing happily. The sun has been tormenting me for a week now. I’ve bought a sleeping mask but it doesn’t make any difference. At night I’m not sleep-ing a wink. And when I walk to the toilet block at night, the sun shines on my sleepy head, and I can hear the birds singing softly.

Fallen tree in Pasvik National Park.

the policepost

The next morning we drive to the end of the road. According to the map, this is the village of Ny-rud. Here, Norway ends and Russia begins. In fact, the natural park extends over both countries; it is the most north-westerly point of the enormous belt of taiga that spans the north of Russia. This is one of the few places in Europe with virgin taiga. These forests have never been planted or re-placed; they have always stood here. There are few border crossings – a relic of the Cold War, and probably of the fresh tensions too: it is here that NATO borders directly on Russia. The village of Nyrud appears to consist of a single house: a police station. Just like all government buildings, the police station is exceptionally well maintained, and surrounded by a lawn that has been so pains-takingly mown that it would make even a Swiss man jealous. This is the home of the policeman Arild Lyssand. He is unsurprised to find us knocking at his door and he invites us to have a cup of coffee in the garden – something I’m unable to refuse after yet another sleepless night.

It is the end of May, and in this polar region it’s supposed to still be spring, but we’re sitting out-side in a T-shirt. Lyssand repeats what we keep hearing: the winters are shorter, and everything is happening a month earlier. The thaw, the blossom, even the mating season is starting earlier.

This is a desirable police station in Norway, and many policemen apply to be posted here. Before this, Lyssand worked even further north, in Spitsbergen, so this must feel like the Riviera to him. I ask him why this police station exists, given that no one lives here. Lyssand points to the other side of the river, which runs past the immaculate lawn. ‘That is Russia. This police station is our way of showing that this is Norwegian territory.’ He points to a large Norwegian flag. It hadn’t been ob-vious at first as there’s no wind and the flag is hanging limply against the pole. Lyssand talks about an expedition with Russian border officials, the week before. Together they went into the nature reserve that covers both countries. In this way, they try to maintain a dialogue with their eastern neighbours.

I walk to the river. The bank on the other side is close enough for me to be able to see buildings or people, but there aren’t any. The trees, rocks and birds are the same, but in a different country. During the five years that I spent in Russia, it would never have occurred to me to pop into a police station for a chat. ‘I don’t like Putin because he tells other people what to do,’ someone remarked earlier in the week. The authoritarian Russia of Putin is worlds away from the egalitarian Scandinavia. Where a policeman invites you in for coffee.

We drive back to the campsite, and hear the sound of a machine. Our neighbour appears to have a sawmill. As soon as we walk into the yard, a dog starts barking, but this is drowned out by the noise of the saw. The neighbour continues to focus on his sawing. He puts the long trunks in a clamp and then pushes them against the circular saw, which slices through the wood like butter. Only when the entire trunk has been turned into planks does the neighbour notice our presence. His name is Ben-Arne Sotkajærvi and he saws wood for the whole valley. As well as being a sawy-er, he is also an amateur photographer, and a local celebrity amongst nature photographers.

Anyone who lives in the valley can get a permit to fell trees. You tell the local authority which tree you want to fell, and then someone comes to check that this won’t cause a problem with the sur-rounding plants, for example a rare flower. Snow scooters drag the trunks to Sotkajærvi, who saws them up in spring: the highest quality parts become planks, the rest sawdust. It’s difficult to take in, but Sotkajærvi is operating the saw on his own. He is proud to show us around his workshop; he is one of the few people who still knows how to steam bend a wooden plank, a process that involves an enormous clamp and boiling water. In the corner is a barrel full of pitch for a different process. Everything has been handmade with love and care, from the lamps above the table to the toilet seat. And everything is made of wood. From the age of four, Sotkajærvi’s father and grand-father taught him to work with wood. He built his first sauna at the age of fourteen.

Sotkajærvi invites us to go for a walk in search of brown bears in the forest, which is one of the few places in Europe where they have always lived. After he’s sawn up the final tree trunk, we drive into the forest. By that point it’s eleven o’clock in the evening. We make a lot of noise so that we don’t frighten the bears. Last winter, a female bear with three cubs attacked a woman who was walking her dog in the forest. The bear was subsequently shot dead.

You can see from the way the sawyer walks through the forest that he has been coming here since childhood. He casually points out prints that are invisible to the untrained eye. A tree stump in which a bear’s claw has been digging, in search of ants. A black fungus growing on a tree trunk that you can cook and drink for medical purposes. It is almost midnight, but rays of sun are pene-trating through the mist that’s hanging in between the pine branches. I ask Ben Arne if he isn’t inclined to get gloomy in winter, when the sun doesn’t rise for three months. ‘People think that the winter can be depressing. But in fact the light at that time of year is fantastic. Fifty shades of grey,’ he jokes. ‘The sun doesn’t come up above the horizon, but there is a gloaming. A kind of eternal sunset. Much more interesting than this sun,’ and he points to a watery sun that is hanging above the treetops, despite the fact that it’s midnight.

We end up in a swamp. ‘In a few months’ time you can’t stand here, because the mosquitoes will have taken over,’ Sotkajærvi says. Tonight there are no mosquitoes. Nor are there bears. We con-tinue walking through the forest and every time we stop walking to listen for bears, silence encir-cles us.

At one o’clock in the morning we are back at the campsite. Finally, after four sleepless nights and the night-time forest walk, I have the sense that tiredness has gained the upper hand. I clean my teeth in front of our little hut and look over at the other side of the river, where Sotkajærvi has his sawmill. He’s walking across his land with a huge, droning lawnmower. He nods to me cheerfully, as if mowing your lawn in the middle of the night is the most normal thing in the world. And in these parts, that may very well be the case.

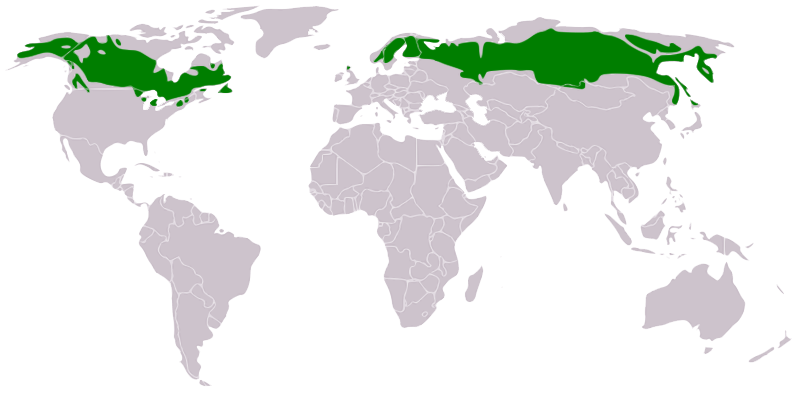

The boreal zone

The boreal forest is the largest vegetation zone on earth and comprises some 29% of the total forest area. With a surface area of some nine million square kilometres, it is considerably larger than the Amazon rainforest. Particularly in Russia, deforestation has increased dramatically since the fall of communism.

Boreal forests convert carbon dioxide into oxygen on a large scale. The average tree produces enough oxygen over a hundred-year period to allow a person to breathe for twenty years. Yet less than twelve per cent of these forests have protected status.

Due to climate change, the world of trees is changing. These changes are especially noticeable in the High North. For example, in 2016 the temperature in parts of Arctic Russia rose to between 6 and 7 degrees above the average.

The Borealis-project is supported by ASN Bank, Staatsbosbeheer (State Forest Management) and the Anchorage Museum in Alaska. Trouw is media partner. You can also support the project. More information at borealisproject.nl

WRITTEN BY: JELLE BRANDT CORSTIUS

PHOTOGRAPHY: JEROEN TOIRKENS

WEBSITE: CHARLOT VERLOUW thanks to JAN KRUIDHOF