The Forest Fires

in buryatia

Tackling the flames togethe

From the Amazone to the North Pole: forest fires rages all over the world last summer.

In Siberia, volunteers go to the aid of the overstretched fire service. .

the forest fires of buryatia

From the Amazon to the North Pole: forest fires raged all over the world last summer. In Siberia, volunteers help to fight them.

Journalist Jelle Brandt Corstius and photographer Jeroen Toirkens visited the northenmost forests of the world. Four years, eight trips. Find other episodes of this journey here. Jelle elaborates on the project in this video.

‘In recent years the weather has been in disarray. Dry lightning, which causes the fires in the re-mote areas, is increasingly common. And it hasn’t rained since mid-June, so in July the fires just carried on burning. It’s global warming, right’, says Grigory Serdyukov as his phone rings again. Serdyukov is the director of the local office of Aviales, the Russian service responsible for putting out fires from the air. This service attempts to fight the most remote forest fires from the air. Ser-dyukov is an energetic young man and that’s just as well, because during the interview his phone rings every thirty seconds.

Aviales is responsible for putting out fires in the areas that the fire service cannot access with trucks, the so-called ‘control zones’. The Russian government created these in 2015. These are remote areas where fires — according to the government — cannot do any ‘economic’ damage and are in principle not extinguished, unless things get out of hand. And this year, things are getting seriously out of hand, Serdyukov tells us. He shows us a map of Buryatia with 170 dots on it. Each dot is a large fire. Firefighting in this remote area is done by dropped parachutists, around seven of them, armed with a chainsaw, a pump, fire extinguishers and provisions for about ten days. They create fire corridors in the wilderness and if necessary, they put out the fire.

Serdyukov’s office is at the edge of Ulan-Ude, the capital city of the Russian republic of Buryatia, at the point where the city runs into the endless Siberian forest. The fires start in the spring and there is normally a pause in July, when rain puts out the majority of fires. Serdyukov is responsible for fighting fires in Buryatia, an area about the same size as Germany, situated to the south and east of Lake Baikal.

It’s early August and Russia is on fire. Forest fires are a natural phenomenon, necessary for the health of the forest. But the scale on which the forest is currently burning is abnormal: up to now, an area around twice the size of the Netherlands has gone up in flames, and it is still burning. The average temperature in Siberia in June was 10 degrees above the average measured between 1981 and 2010, the World Meteorological Organisation reports. This created the ideal conditions for forest fires.

Not only is there a greater risk of fires due to a warming earth, but the fires themselves also bring about further warming. All the carbon stored in the trees is released in one fell swoop. During the Siberian fires this summer, around 166 megatons of CO2 has been released up to now — more than the total emissions of the Netherlands in 2018. In addition, many soot particles settle on permanently snow-covered regions in the Far North. The layer of soot means that the sun reflects less well and the ground retains more heat, which in turn leads to yet more warming.

Mikhail Zubov, pilot and observer from Aviales, in the Antonov that’s being used to find fires in an area the size of Germany. Old army helicopters are being used as well.

S

erdyukov allows us to fly with the men from Aviales. We are sitting in an antique Antonov plane, which is going to drop provisions for a group of parachutist firefighters in the remote forest of a nature reserve. They have been putting out the fire for ten days now, and their food supplies are almost exhausted. We fly over the delta of the Barguzin River, and the pilot points to thin lines beside the river. These are apparently bear paths. I asked him when he last had a day off. ‘In May!’ the man laughingly shouts.

The smell of smoke in the air is becoming stronger — so we are nearing the dropping site. The fire has been contained and they are now engaged in damping down, but a huge area has burnt out. All sense of scale vanishes. Only when we fly over the parachutists’ miniscule tents do you get an idea of how much forest has burned there.

I

t is clear that the overworked men of Aviales cannot do this alone. In the centre of Ulan-Ude, Len-in still stands on the central square, in this case in the form of an enormous head that is three sto-reys high. Not far from the statue, Andrej Borodin has an office in a small room of a school for disabled children. Borodin leads a group of volunteers who are fighting the fire. That is unusual in a country where most people regard it as the state’s responsibility to solve problems — a legacy of the Soviet Union.

Borodin is a Buryat, a people that are related to their southern neighbours in Mongolia. He proud-ly shows us the flag of Buryatia, which sports three flames representing the past, the present and the future. ‘It is for this third flame, the future, that I’m doing my work’, Borodin tells us. ‘I used to work for the government, and I saw that the state could not cope with the scale of the fires. Often, the problem was not money, but poor information provision. The authorities constantly promised to put out the fires but then it didn’t happen. Residents were left feeling powerless.’

Borodin’s organisation helps pinpoint and report fires, and if necessary, helps put them out. In addition, with the aid of Greenpeace, the volunteers provide information on fire prevention: ‘Seventy per cent of the fires are caused by human activity. Many farmers still set fire to grassland in spring because they believe that it makes the soil more fertile. A large number of forest fires start in this way.’

Borodin also fights against illegal logging, which is a lucrative trade with China and its endless demand for wood. Borodin: ‘These loggers only take the planks with them. They leave the bark and sawdust behind, and this acts like gunpowder in dry conditions. It catches fire, or they set fire to it themselves to cover up their activities.’

Volunteers during a practive, organized by Greenpeace.

Volunteers during a practice, organized by Greenpeace.

We visit the annual camp for the volunteers, where they learn how to put out fires in just under a week. This is the fourth year that the camp has been staged. It is set up between the conifers on the edge of Lake Baikal. Above the fire simmers a cauldron of buckwheat and tushonka, stewed pork from a can. The participants have come from all over Siberia. Jelena Belova is from Krasnoy-arsk.

‘I joined the volunteers after the big forest fires of 2015. That year the smoke pollution was terri-ble and this year it’s the same. The authorities’ reaction is always to say there is nothing wrong. But the problem with a forest fire is that you cannot hide it.’

Across Siberia, people took to the streets this summer to demonstrate against the government’s tardy intervention. They demanded the resignation of those in power locally — highly unusual in a country where people customarily accept things with resignation.

Ekaterina Groedinina of Greenpeace has also noticed that Russians are no longer looking on hel-plessly. ‘This summer, we started up a petition to force the government to fight the forest fires more effectively. In no time at all, the petition had attracted 400,000 signatures. This is how we keep up the pressure on the Russian government.’

So how could the government fight these fires more effectively? Groedinina: ‘More fire prevention, and earlier intervention in forest fires. It is always possible to fight a fire effectively if you get to it early.’

One of the course leaders is Solbon Sandgiev, an imposing Buryat in worn overalls with a helmet and walkie-talkie. Every now and again, one of his children jumps onto his knee. He tells us that the number of participants at the camp is increasing every year. ‘More and more Russians are aware of the effects of global warming due to these forest fires. In the past twenty years, the number of forest fires in this region has increased, and the fires have also become bigger.’

And yet the volunteers are winning some small victories, chiefly in fighting the peat fires that are difficult to put out and that often go on burning for months. Also, they are successful because they consult with the professional emergency services. ‘This is unique for Russia. In Buryatia, we have a commission where volunteers collaborate with professional firefighters, forest rangers and staff from the Ministry of Emergency Situations.’

Sadly this is still an exception in Russia. It is often unclear who precisely is responsible for monito-ring or putting out a fire, which means that in practice nothing happens. Sandgiev: ‘First my friends said: “You can’t change the system, you’re mad.” But in the past four years, we have pro-ved that we can make a difference.’

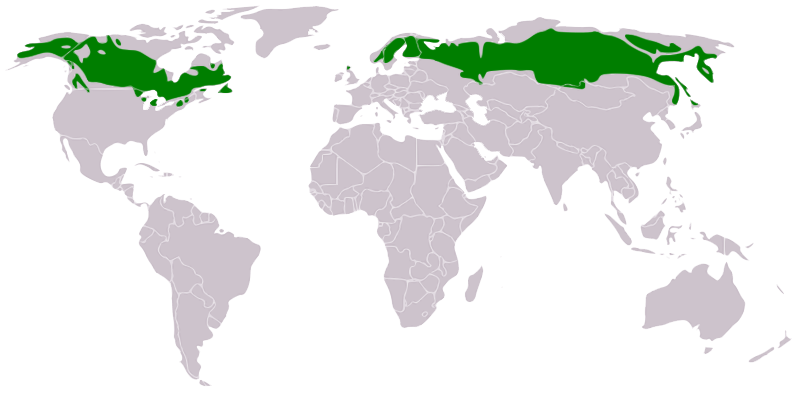

The boreal zone

The boreal forest is the largest vegetation zone on earth and comprises some 29% of the total forest area. With a surface area of some nine million square kilometres, it is considerably larger than the Amazon rainforest. Particularly in Russia, deforestation has increased dramatically since the fall of communism.

Boreal forests convert carbon dioxide into oxygen on a large scale. The average tree produces enough oxygen over a hundred-year period to allow a person to breathe for twenty years. Yet less than twelve per cent of these forests have protected status.

Due to climate change, the world of trees is changing. These changes are especially noticeable in the High North. For example, in 2016 the temperature in parts of Arctic Russia rose to between 6 and 7 degrees above the average.

The Borealis-project is supported by ASN Bank, Staatsbosbeheer (State Forest Management) and the Anchorage Museum in Alaska. Trouw is media partner. You can also support the project. More information at borealisproject.nl

TEXT: JELLE BRANDT CORSTIUS

PHOTOGRAPHY: JEROEN TOIRKENS

WEBSITE: JORIS BELGERS thanks to JAN KRUIDHOF