Canada, wind chill temperature -55

The indiginous Cree can no longer live from hunting, so they are selling their trees. What does that mean for their future?

Journalist Jelle Brandt Corstius and photographer Jeroen Toirkens visited the northenmost forests of the world. Four years, eight trips. Find other episodes of this journey here. Jelle elaborates on the project in this video.

These are historic images. It is 1976 and commercial seal hunting in Canada is in full flow. A man casually approaches a helpless seal pup, who is unaware of the impending danger. He strikes with his hakapik, the traditional weapon of the Inuit in the north of Canada. A single blow and the pup is dead. The man drags the pup away, leaving a trail of blood in the fresh snow. Thanks to Green-peace, these images went around the world in 1976. This was Greenpeace’s first successful cam-paign, and the pressure group would then grow into the most recognisable environmental organi-sation in the world. For the Inuit, it was a disaster: trade in sealskins was banned and thus their key source of income dried up. Unemployment, alcoholism and suicide were common. Indeed, in 2014 Greenpeace apologised to the indigenous peoples of Canada.

The impact of the images was felt far beyond the Inuit alone. A thousand kilometres to the south, where the indigenous Cree live, the prices of beaver and marten skins also nosedived. The traditi-onal way of life in the wild was threatened, and numerous Cree went back to the reserves. The traplines, the traditional hunting grounds of the Cree, fell into decline. Each trapline comprises around 700 square kilometres, the area that is necessary to supply a family with enough game to survive. Logging companies seized the opportunity: they purchased the right to extract wood from the traplines. This was mostly done by clear-cutting: the uniform felling of all the trees in a forest. Ultimately 90 per cent of the forest disappeared in this way. All that remained was a cleared area, surrounded by an intricate road network for transporting all those trees.

Just three of the 52 traplines are untouched. The question is how long these forests will continue to exist. The journey to these regions begins at Waswanipi, an eleven-hour drive north of Mon-treal. This small town with its 1300 residents is the capital of Eeyou Istchee, the land of the Cree, an area about the same size as the Netherlands. Steven Blacksmith from the local Ministry of Na-ture and the Environment is leading our expedition to the Broadback Valley, one of the last places where the ancient forest is still standing. Men are busy loading up sledges with provisions and fuel. A gigantic freezer, which amusingly enough is designed to ensure that the food does not free-ze, is also packed full. Snow scooters are made ready, but we have to drive them ourselves. ‘This is how you accelerate and this is the brake’, is the short explanation we are given. Before we realise it, the Cree have disappeared over the horizon. Fortunately their tracks in the snow are easy to follow.

The 150-km journey takes us through the boreal forests of Northern Canada. Here there is little clear-cutting to be seen. The trees in this area were cut down thirty years ago; in the meantime a new generation of conifers has sprung up from the earth.

Eight hours later, we arrive at the house of Don Saganash, in the heart of the Broadback Valley. As tallyman, he is in charge of the three traplines where the forest has not yet been felled. In the meantime, the temperature has dropped to minus 40 degrees Celsius, and each time someone opens the front door, it is as if they are opening the door of a giant freezer.

In the back room, Saganash throws some more wood on the stove. He points to the nails in the floor, which despite the heat are covered with ice. ‘I haven’t experienced this for some time’, he laughs. He tells us about his fellow-tallymen, who have sold their forests. ‘Many of them were se-duced by the sums of money that the companies were offering. Of course it means a profit in the short term, but in the long term their land and their traditions disappear’, says Saganash.

But what is the situation with the planted forests that we have seen on the way to the Broadback Valley, I ask him. ‘We are hunters. We hunt moose and reindeer. But they don’t like these forests. There’s not enough moss for them to eat. A forest is far more than just trees. It takes longer befo-re the fragile forest floor is restored. And it takes even longer before the fungi and lichens have repopulated the forest. Every animal is dependent upon this ecosystem.’

‘A forest is more than trees’

The freezer is opened again and in a cloud of condensation, three enormous Cree step inside. They take off their layers of clothing like Russian dolls and hang them up to dry by the stove. Saganash greets them in Cree. ‘A year before he died, my father made me tallyman’, he tells us. ‘He said to me: “Make sure that you keep the logging companies out of our forest.” I have never forgotten that.’

The moment of reckoning came after his father’s death: ‘It was a Wednesday morning. I was sit-ting in a small office with three men. They offered me a house for the Broadback Valley. I said no. Suffice to say that’s not what they were expecting!’, says Saganash and he bursts out laughing. He points outside, where it is now pitch black. Where his father went hunting, and his grandfather before that.

Saganash found an unlikely supporter in Greenpeace, which until recently was unpopular with the Cree community because of the seal campaign. This has now changed. Together with Greenpeace, Saganash is trying to make the three traplines that are still intact into a nature reserve, so that felling will never be permitted. The stove is well stoked once again before the night begins, and after that everyone rapidly falls asleep, exhausted from the long journey. During the night I awake from time to time when Saganash climbs out of bed to put some more wood on the fire. I see his determined face glowing in the flames of the stove.

Below a 360-picture of the room. Swipe left or right to watch the full room.

Below a 360-picture of the room. Drag your mouse left or right to look around.

The next day, it is too cold to cross over the lake to the Broadback River. There is a strong wind blowing on the lake, and the wind-chill temperature has fallen to below 55 degrees Celsius. A number of the Cree are showing symptoms of frostbite. I can no longer feel my little fingers. We are confined to the house and the direct surroundings. Only the young people dare to go out in the cold. Outside Donovan Blacksmith beckons to me and points to a small pine tree. ‘Don’t you see it?’ He cocks his rifle. The shot cracks through the freezing air. Lying at the foot of the tree is a ptarmigan. Only the blood allows you to make it out against the snow. I am reminded of the baby seal. Donovan plucks the bird on the spot, and its feathers are carried away by the icy wind. He prefers hunting moose, he explains. ‘Living off the land, what could be better than that?’

Inside, Steve Blacksmith smiles over at Donovan. ‘Next year I’m taking a sabbatical. Then I’ll retre-at to my hut in the bush and I’ll live on what the land gives me.’ I ask Blacksmith about his youth. I had heard that the Cree children were forced to go to boarding school, and understood that it was sometimes pretty harsh there. By removing them from their parents, they could be more easily assimilated into Western culture, was the idea. The last boarding school closed as recently as 1996. Blacksmith confirms that, whilst at the same time making it clear that he has no desire to talk about it. More than six thousand children died in these boarding schools due to illness or mal-nourishment, according to the Truth Commission that is investigating the abuses.

Johnny Picard joins us at the table. He was ‘adopted’ by the Cree but hails from the neighbouring Innu. After his brother died of an overdose, he went to try his luck with the Cree. The suicide rate is still higher there than elsewhere in the country. ‘Did you know that the Cree don’t even have a word for suicide? In the past, it simply didn’t happen’, Saganash remarks bitterly.

‘Did you know that the Cree don’t even have a word for suicide?’

The following day, the wind has died down somewhat and the temperature has risen to a Mediter-ranean minus 25 degrees Celsius. We cross the lake and chug on to the place that Don Saganash has already been talking about for two days: the mighty Broadback River. From the lake, a portage runs to another lake: a long-established pathway through the forest through which canoes could be moved between two lakes. Saganash points out a notch in the trees. Every generation makes a new notch, so that the route through the dense forest is not lost. ‘Logging is not the only problem; the roads are too. They cut across these kinds of routes. And across animals’ migration routes.’ After a difficult journey on the portage, at the edge of the next lake the sweat in my ski goggles has frozen solid and I can now see next to nothing. Once again, I have fallen hopelessly behind. Saganash and the other Cree have long since crossed the lake. I am left alone, surrounded by the pines and the silence.

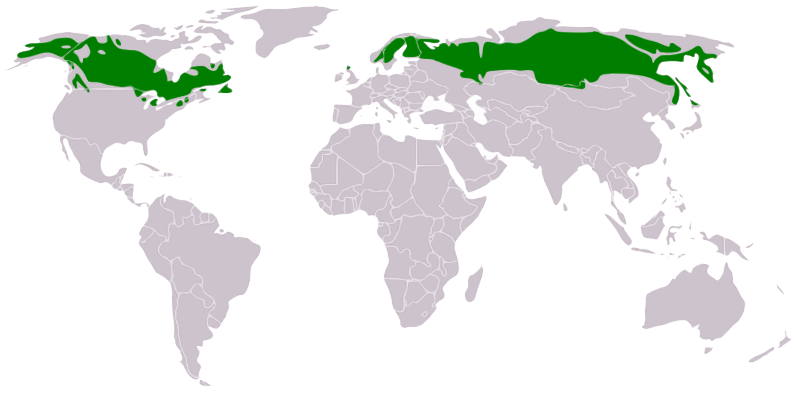

The boreal zone

The boreal forest is the largest vegetation zone on earth and comprises some 29% of the total forest area. With a surface area of some nine million square kilometres, it is considerably larger than the Amazon rainforest. Particularly in Russia, deforestation has increased dramatically since the fall of communism.

Boreal forests convert carbon dioxide into oxygen on a large scale. The average tree produces enough oxygen over a hundred-year period to allow a person to breathe for twenty years. Yet less than twelve per cent of these forests have protected status.

Due to climate change, the world of trees is changing. These changes are especially noticeable in the High North. For example, in 2016 the temperature in parts of Arctic Russia rose to between 6 and 7 degrees above the average.

The Borealis-project is supported by ASN Bank, Staatsbosbeheer (State Forest Management) and the Anchorage Museum in Alaska. Trouw is media partner. You can also support the project. More information at borealisproject.nl