At the heart of Russia’s

wood industry

At the heart of

Russia’s wood industry

In the north of Russia lies the largest forest in the world.

Journalist Jelle Brandt Corstius and photographer Jeroen Toirkens visited the northenmost forests of the world. Four years, eight trips. Find other episodes of this journey here. Jelle elaborates on the project in this video.

G

ennady Tugushin is sitting in his container, at the crossroads between two roads. Gennady is his official first name, but everyone simply calls him Gena. It is freezing outside, but in the container a stove is providing heat, and a TV provides the entertainment. The main road runs from Kotlas to Syktyvkar. The other road is a private road belonging to the forestry company. The road is reinfor-ced with concrete slabs, which is necessary, because the only vehicles driving along it are lorries heavily laden with wood.

Gena works as a guard for the forestry company. From here he can keep an eye on everything: who is driving into the forest and who is coming out. Every lorry with a load of wood has to stop briefly at the container so that he can check whether the load of wood is securely lashed down. ‘It can be life-threatening’, Gena explains. ‘Last week, another lorry toppled over because the wood wasn’t correctly balanced.’

Gennady Tugushin still works for the wood company.

Gennady Tugushin still works for the wood company.

We drive to the port of Soyga, from where the thicker trunks set off for the port of Archangelsk. From there, all the wood goes by boat to the sawmills in the spring, when the Vychegda River has thawed. ‘I need to check that nothing is stolen, or that fire has not broken out. As soon as there is a fire, you lose all your stock’, Gena says with a cigarette butt dangling from his mouth.

The more slender trunks end up in the local pulp mills, after which they are made into paper. This paper is destined for the European market, and the volume keeps on growing because thanks to the weak rouble, the demand for Russian paper is high. As well as being a big player in oil and gas, Russia is also a paper giant. The reserves are huge: there is a belt of Boreal Forest growing almost uninterrupted across the entire width of Russia. Around one fifth of the world’s trees are growing in Russia, which is therefore the largest forest owner in the world, even larger than Brazil with its Amazon Rainforest.

The overwhelming majority of this forest is unsuitable for logging, because it is quite simply too far from the road. But here, between Kotlas and Syktyvkar, conditions are perfect: 85 per cent of the economy here revolves around forestry. There is a good road network, a river on which the wood can be transported, and people living here who can do the work. More than 800,000 Russians work in forestry and Gena is one of them.

In fact he has already retired. He worked as a logger his whole life, but in order to supplement his meagre pension he has stayed on as a guard, mostly working night shifts. His face shows signs of a hard life. ‘It was back-breaking work, it kept going all winter. Only when the mercury dropped to below 40 degrees Celsius did we get a day off. In the Soviet era, there were no heavy machines; everything was done with a chainsaw.’

He takes us with him to his house, in the village of Berdyshikha, fifteen minutes’ drive from the container. He parks his car on the edge of the road beside the turning to his village, as we shall be doing the final kilometre on foot. ‘It’s going to snow quite heavily tonight, and if it really snows, I won’t make it out of the village tomorrow. They keep the main road clear because of the wood transports, but they don’t always have time to drive into the village.’

The village looks empty, with smoke rising from just two chimneys. His own house stands at the end of the road. A radio hangs in a tree in the snowy garden, playing at full volume. It seems to be designed to dispel the silence. Proudly he shows us the banya, the Russian sauna, and his rabbit hutch. ‘The first time I had to slaughter a rabbit, I cried, but after that never again. Rabbit meat is good for your health, especially if you are a little older’, he explains.

Inside, as Russian hospitality dictates, his wife Tonya has prepared a table full of delicacies. Almost everything comes from their vegetable garden and the forest on the other side of the river. In the winter there is not much to do, but in the summer the couple work long hours, and the midnight sun comes in handy. Vegetables from the garden, mushrooms, berries and birch sap from the fo-rest, and a fish from the river. They never go into the forest alone: ‘You never know what you might encounter. There are snakes and bears. From time to time you find yourself picking raspberries from the same bush as a bear. But we leave each other in peace. You have to respect the forest and the animals. The forest feeds you, gives you oxygen. What more do you need?’

‘Only when the mercury dropped to below 40 degrees Celsius did we get a day off’

‘The only thing we buy in the shop is sugar, otherwise I can’t make brandy’, Gena says. Tonya fet-ches an enormous preserving jar with brandy from the cellar, which also contains row upon row of preserved vegetables to see them through the winter.

Naturally, Gena gets wood from his company. A lorryload every year to get through the winter. Without wood, life is impossible in Russian villages. The stove is at the heart of the home, and is typical of Russian village houses. It is a huge brick monster. The rooms all adjoin the stove, so everywhere is pleasantly warm. ‘When I get really old, this is where I’ll end up’, Tonya says, poin-ting to the top of the stove. Elderly Russians lie on the stove, the warmest place in the house, in between the felt boots that they put there to dry.

Two televisions are on throughout the day; one for Tonya in one room, and one for Gena in the other. Gena’s TV is permanently tuned to the First Channel, a state broadcaster where viewers are bombarded with propaganda all day long. According to Gena, Russia is surrounded by enemies and everyone is set on destroying Russia. This is precisely what the Kremlin does: blame all inter-nal problems — for example the fact that Gena has to keep on working to supplement his pension — on foreign politics.

When Gena starts getting really hot under the collar, Tonya comes out of the other room to divert attention with a glass of brandy. ‘Do you want to see my children?’ Tonya asks, and she takes me with her to a windowsill on the south side of the house. Standing there are small pots with baby tomato plants, which have only just germinated. In this way she manages to extend the growing season a little. In May, when most of the snow has melted, the tomatoes can be planted out in the greenhouse.

Tonya hails from Donetsk, in Eastern Ukraine, where the war is now raging. With her Ukrainian passport, she cannot work in Russia, so she takes care of the household. ‘Of course I miss my friends and city life. Going to the cinema, wonderful! But I can’t go back, there is war. And anyway, I’ll never persuade Gena to move to the city.’

The following morning, Gena knocks on our door. The snow has been cleared on the main road and he wants to take us with him to the loggers. We drive fifty kilometres through a forest that was already cut down and replanted in the Soviet era. The trees are not yet mature enough to be felled. Replanting trees is a big problem in Russia. Although new trees are planted on a grand sca-le, they are not well cared for afterwards. This will become a problem in twenty years’ time, when they need to be felled, but the question is whether many of them will still be standing.

We arrive at where the loggers are. Despite the freezing cold, it is easier to work than in the sum-mer, when the mosquitoes make working nigh on impossible.

Darkness falls. Enormous vehicles with work lights crawl through the forest like monsters, about fifty metres away from us. We are not allowed to come any closer. At intervals, you see a pine disappearing into the jaws of one of the monsters, which effortlessly fells it, strips it of its bran-ches and throws it onto the ground like a matchstick. To start a new life as a cupboard, table, newspaper or tissue.

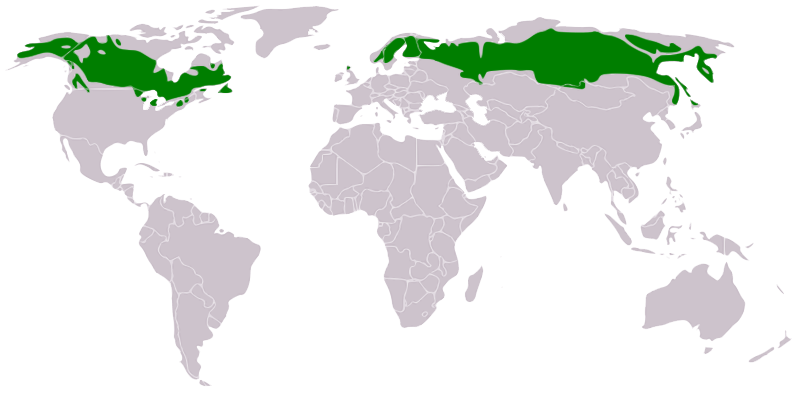

The boreal zone

The boreal forest is the largest vegetation zone on earth and comprises some 29% of the total forest area. With a surface area of some nine million square kilometres, it is considerably larger than the Amazon rainforest. Particularly in Russia, deforestation has increased dramatically since the fall of communism.

Boreal forests convert carbon dioxide into oxygen on a large scale. The average tree produces enough oxygen over a hundred-year period to allow a person to breathe for twenty years. Yet less than twelve per cent of these forests have protected status.

Due to climate change, the world of trees is changing. These changes are especially noticeable in the High North. For example, in 2016 the temperature in parts of Arctic Russia rose to between 6 and 7 degrees above the average.

The Borealis-project is supported by ASN Bank, Staatsbosbeheer (State Forest Management) and the Anchorage Museum in Alaska. Trouw is media partner. You can also support the project. More information at borealisproject.nl

Text: JELLE BRANDT CORSTIUS

Photography: JEROEN TOIRKENS

Website: DANUSIA SCHENKE EN JAN KRUIDHOF